Seeing a kid begging or working on the streets is a common sight in Manila. In fact, there is an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 street children living in Metro Manila. The streets shouldn’t be a place where these kids grow up, but that is the harsh reality.

Thankfully, there are efforts aimed to help these children and young people at risk who are mostly out of school and exposed to a life of crime. Most of these efforts are focused on providing these children food and shelter, but a group in Manila is taking another approach. They’re the Capoeira Angola School ECAMAR Philippines, a cultural non-government organization. Through their Project Bantu Philippines program, they aim to use Capoeira Angola to help at-risk children at risk develop self regulation, awareness, and other values.

What is Capoeira Angola?

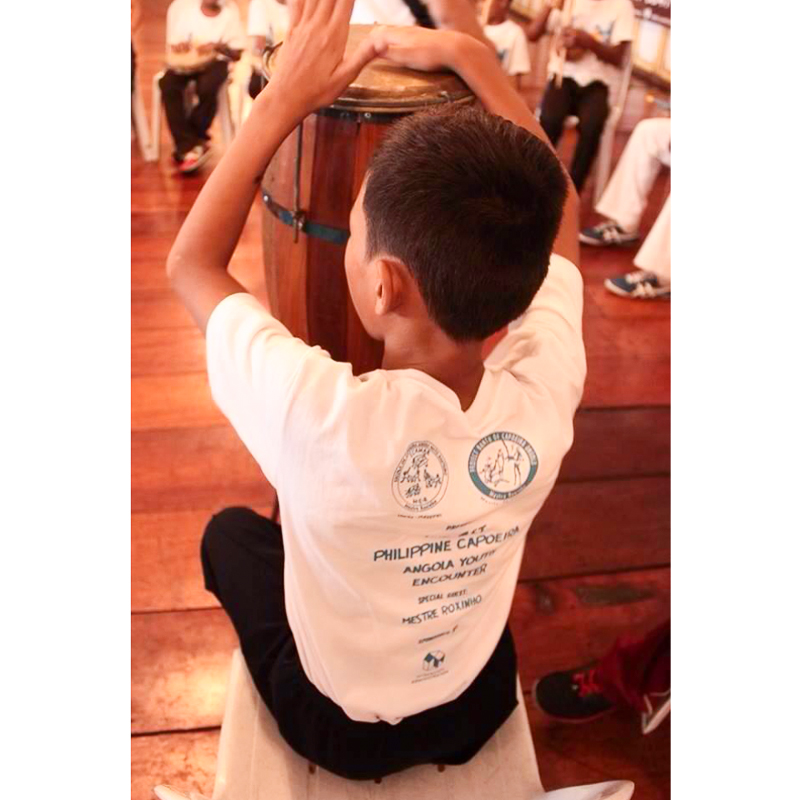

Capoeira Angola is an art, rich in tradition and philosophy. It has many elements, one of which is a dance that mimics the movements of animals and phenomena from nature. Another element is music. Practitioners of this art form play traditional instruments like the African Berimbau and sing traditional songs from Capoeira’s history.

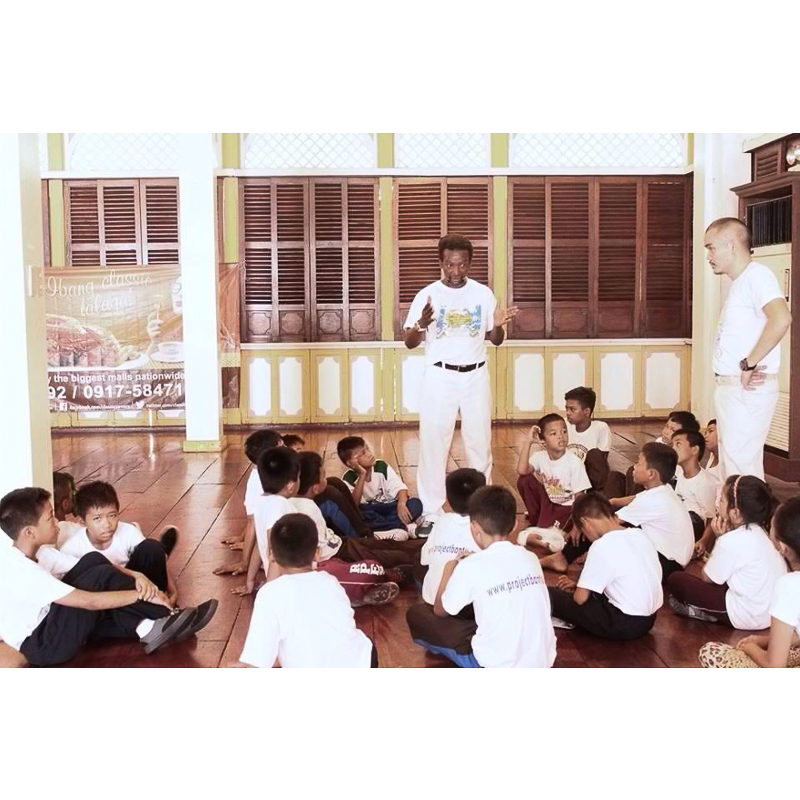

Mestre Roxinho talks to participants of Project Bantu Philippines about Capoeira Angola. | Photo by Project Bantu Philippines

According to Jaime Leandro Benedicto, the director of Project Bantu Philippines, Capoeira Angola helps the street children with their socialization and how they understand the world around them.

“Higit na importante itong mga kanta, kasi sa loob ng kanta makikita natin ‘yung kasaysayan, ‘yung mga leksyon na pwedeng ituro sa mga bata tungkol sa buhay, kung paano nila maintindihan ‘yung mga nangyayari. So, importante ito lalong lalo na sa mga bata na walang pagkakataong mag-aral, walang pamilya, walang magulang na magtuturo sa kanila,” he said.

(“The songs are very important, because within them we find the history, the lessons that can teach young people about life, that give them a way to understand the things that happen around them. So, it’s especially important for the kids who have not had the opportunity to go to school, those are separated from their families, who don’t have their parents to teach them these things”, he said.)

Two participants of Project Bantu Philippines immersed in a game while their other friends cheer on. | Photo by Project Bantu Philippines

Project Bantu Philippines also gives the children a chance to perform with practitioners of Capoeira Angola and mentors like Mestre Roxinho, a world-class Capoeira Angola instructor from Bahia, Brazil. During these exercises, which they call “games,” the children are treated as equals by their mentors.

Mestre Roxinho partners with a young student during a Capoeira game. | Photo by Project Bantu Philippines

“Nakakataas din ito ng self-esteem nila kapag may nakakasama silang mga international na guests, mga nakatatanda. Makikita nilang pareho lang pala ang ginagawa nila, marunong din sila tumugtog ng instrumento, minsan mas magaling pa sila. Nakakataas din ito ng self-esteem nila at ng concept nila ng sarili,” Benedicto said.

(“It also raises their self-esteem when they are together with international guests and older students. They see that they do the same things in class, they also know how to play the instruments and in some cases, they are even better than the older ones. This builds their self-esteem and their concept of themselves”, Benedicto said.)

In June 2015, they had the 1st Philippine Capoeira Angola Youth Encounter, where the children from different communities had the chance to interact with Mestre Roxinho and other foreign guests. During this weekend-long encounter, Mestre Roxinho explained that ever since Capoeira Angola was invented by African slaves in Brazil in the 16th century, it was used by disadvantaged people to overcome trauma, anxiety or poverty.

A young student of Project Bantu Philippines playing a traditional African drum. | Photo by Project Bantu Philippines

“Because the slaves speak a different language from one another they found that body movement was a way to communicate and empower themselves and fights against their oppressor, for their rights and freedom,” Mestre Roxinho explained.

It has also become an important tool for inclusion. Through Capoeira Angola, you control your emotions, you control your anger, you control your body skills and you become a sociable person.

Children enjoying the dance exercises or games. | Photo by Project Bantu Philippines

“You also bring the person to a community, a family where they can feel that they belong to something where people don’t judge if you’re poor, white, black, Filipino, or Japanese. Doesn’t matter your age, doesn’t matter your size, doesn’t matter how much knowledge you know,” Mestre Roxinho added.

Children learn how to use the Berimbau, a traditional African instrument. | Photo by Project Bantu

Working with street children

Project Bantu Philippines has been enrolling at-risk children in their classes since 2012. They have two groups of students: one from San Andres in Manila and another in P. Burgos in Makati. These students simply need to show up in their workshop space in Makati. The classes are held every week, on Thursday nights and Saturday afternoons.

They started with just four students but now they have around 20 in total. Their youngest student is just seven years old, and the oldest is 14.

Through their Project Bantu Philippines program, cultural NGO Capoeira Angola School ECAMAR Philippines aims to use the arts to help children at risk develop self regulation, awareness, and other values. | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN

Benedicto said that they’re having trouble gathering the kids because they are transient or keep moving from one place to another. Some of the children they teach are also busy working, begging, selling peanuts or chicharon in the streets. On the bright side, the parents of the children who pursue the classes are very supportive.

International guests and students also playing the Berimbau. | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN

“Yung sa community po, nakausap na po namin ‘yung mga magulang nila, suportado nila. Magandang activity ito sa mga anak nila sa oras na pwede silang gumawa ng ibang bagay (Regarding our work in the community, we’ve already talked to their parents and they support it. It’s a good activity for their kids to be doing at times where they could be doing other things),” he said, referring to the fear of parents that their children might be influenced by gangs or drugs.

Mestre Roxinho showing a move to the participants. | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN

Benedicto made it clear that they don’t give rewards or force the children to attend the classes because they want the children to understand for themselves the value and benefit of attending the classes. He is thankful that the children have their own initiative because they are always excited and they even ask their mentors about the next class.

Mestre Roxinho with a participant during the roda or circle where participants play Capoeira Angola. | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN

Project Bantu Philippines plans to expand their reach by partnering with public high schools in Manila. Their project with the other at-risk children still continues, and Benedicto says that their focus is still on education. He hopes that these children will enter formal education and those that are already studying will get to finish college. He says they are also willing to help parents find sponsorships or scholarships, but for now, they do what they can with their lessons.

The dance moves mimic fighting moves and the movements of nature and animals. | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN

“Hindi naman ito magdadala ng pagbabago sa kanila kaagad, pero may nakikita na tayong mga pagbabago. Makikita kasi natin for example sa isang batang ‘di nag-aaral na maalala lang nila ‘yung mga pangalan ng mga ginagawa nila o ng instruments, ‘yung mga kanta sa wikang Portuges na kaya nilang kantahin. Para sa akin, iyon ay progress.”

(“This will not change them right away, but we’re already seeing improvements. When we see, for example, in a young person who doesn’t go to school, that they are able to recall the names of the movements we do or of the instruments, they remember the songs in Portuguese that they know how to sing. For me, this is progress.”)

“Makikita nilang pareho lang pala ang ginagawa nila, marunong din sila tumugtog ng instrumento, minsan mas magaling pa sila. Nakakataas din ito ng self-esteem nila at ng concept nila ng sarili,” says Jaime Leandro Benedicto, director of Project Bantu Philippines | Photo by Nicko de Guzman/MP-KNN